We are all familiar by now with the various efforts that are underway to govern what we are allowed to say, and share, online. But this is a much bigger problem than is commonly perceived – it goes far beyond the ‘mere’ suppression of misinformation or disinformation, as misguided and dangerous as that effort is. What it represents is in fact a problematisation of information

as such. Increasingly, those who govern us simply take the view that it would be better if we had the minimal necessary supply of curated information, carefully vetted by experts, in order that we should arrive at the decisions they deem to be appropriate.

(Article by Dr David McGrogan republished from

DailySceptic.org)

The result is not just suppression of speech through a ‘censorship industrial complex’ but a suppression of knowledge – a deliberate narrowing of our horizons – in the interests of ensuring that a particular moral ‘Truth’ is revealed. This makes it more apt to analyse our era through the lens of political theology than any other conceptual framework.

As I have argued before, we are governed, more and more, by a form of politics that has greater in common with the medieval pastorate than 19th or 20th century liberal democracy – a sort of atheist theocracy rooted in a claim to have sole possession of the knowledge not of what is true or false so much as what is right and wrong.

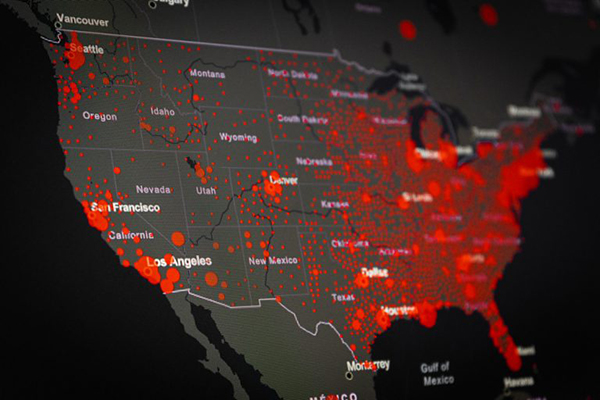

The COVID-19 period (remember that?) should be seen as a crucial turning point in this regard. The war against so called ‘mis/dis/malinformation’ had been being waged for some time before 2020, of course, but it took COVID-19 and the response to it for there to emerge an idea that there needed to be a globally coordinated strategy to

manage information systemically. This was what an international lawyer might recognise as something akin to a “

Grotian moment” – a short phase of rapid change in which a new body of rules or norms develops and gains sudden and widespread acceptance. Before 2020, the chattering classes across the West talked about ‘fake news’ as though it was a problem. After it, governments and international organisations began to collude together in earnest to find methods to establish control over how much, and what, information populations get to consume.

At the heart of this shift was the World Health Organisation (WHO) itself, which

relatively early on after COVID-19 began to spread came to the conclusion that a significant minority of people, on being told to jump, were not asking ‘how high?’ with sufficient alacrity. In April 2020 it issued a “

call for action” in respect of the “COVID-19 infodemic”, and a few months later convened an international event (via Zoom, natch), the

First WHO Infodemiology Conference, as a follow-up. This foregrounded the notion that “infodemic management” ought to be a matter of priority for governments, public health authorities, scientists, academics and so on, and led to the publication of a subsequent ‘

Public Health Research Agenda for Managing Infodemics‘, which itself might be said to have founded “infodemiology” as a matter of academic study. This has now mutated into an entire pseudo-discipline of its own, complete with

training courses,

proposed alterations to curricula for existing educational programmes,

teaching manuals, course ‘

modules’ and so forth.

The portmanteau ‘infodemic’ is asinine, but effectively communicates the basic idea: while an epidemic is a sudden increase in the prevalence of a disease, an ‘infodemic’ is a sudden increase in information

about an epidemic. And, as the generic definition goes (it is the same in almost all documents regarding the subject produced by the WHO), “it spreads between humans in a similar manner to an epidemic” and “makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it”. This is purportedly a problem, because “during epidemics and crises” it is important to “disseminate accurate information quickly” so that people can “take steps to protect themselves, their families and communities against the infection”. There can therefore be only one conclusion: infodemics need to be managed. And a field of study – the aforementioned “infodemiology” – must be devoted to discovering the best ways to manage them.

It is important to be clear about the way in which ‘information’ is conceptualised within this burgeoning field. It is one thing to advocate suppression of information which is false – which is to say ‘mis-’ or ‘disinformation’. There is a whole host of problems associated with doing so, both as a matter of principle and in purely consequentialist terms, and we are all broadly familiar with them: the people who get to decide what is ‘true’ and what is ‘false’ are easily politicised; they are often themselves very badly informed and not particularly thoughtful; they are not usually subject to democratic or judicial oversight; they suffer from groupthink; they fall easily into suppressing opinions they disagree with on the basis of ‘falsity’; I could go on. But the essence of the enterprise of suppressing mis/disinformation does at least rely on an – admittedly childish and naïve application of – a universal human moral standard: it is good to know the

truth rather than falsehoods.

Infodemic management, however, represents something of a step change in that it deliberately sets its face against the petty matter of truth versus falsity in the factual sense. What it is really concerned with is (again, to draw from the generic definition used throughout the WHO literature) “

overabundance of information” (emphasis added). The problem is not people spreading ‘information’ which is false. The problem is people spreading information as such. There is just too

much of it.

Read more at:

DailySceptic.org

Parler

Parler Gab

Gab